The Weight of Gravity

Gravity is a movie of contradictions. It features state-of-the-art special effects that push the boundaries of film technology. Yet this high tech extravaganza also evokes early cinematic technology and experience. It is a film that focuses on bodily experience, taking us on a breathless ride with the (heavily breathing) Sandra Bullock. Yet in other ways this film denounces the human body and its autonomy.

On the other hand, it is a movie of unanimity. Gravity is that rare case of a movie that was generally well received by public, critics and film scholars alike. Critics wielded lofty terms such as “avant-garde” (1) and invoked Derrida and Bazin (2) in their reviews. Famous film scholars described it as an “experimental film” (3) and praised its “poetic exploration of zero-gravity” (4). High praise indeed.

Several years have passed since Gravity blasted off in cinemas, so maybe this is a good time to take another look at the movie and at what made it remarkable. What is its importance in film (and even art) history? Did it herald a new way of filmmaking or did it harken back to earlier episodes of this art form? Those are the questions this video essay tries to address, along the way connecting Cuarón’s movie to abstract expressionist painting and computer chess.

One of the most remarkable aspects of Gravity is how all of its technological wizardry has one foot in the future of film, while the other remains firmly planted in its past. This movie’s allure seems grounded in exactly the same aspects that enticed very early moviegoers: an emphasis on bodily experience and shock value, a strong sense of wonder and a shameless repetition of the same highlights. It is the modern day version of what film scholar Tom Gunning has so eloquently described as the Cinema of Attraction(s), favoring its unique and striking imagery over a strong narrative.

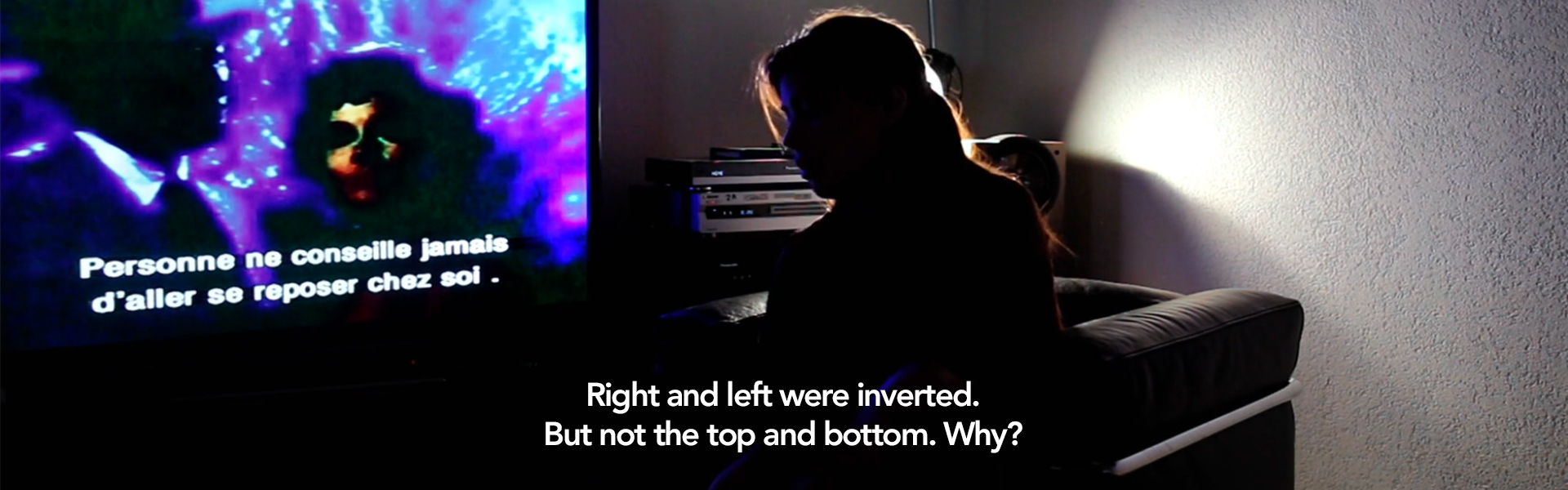

Cuarón creates these extreme images using a blend of state-of-the-art CGI and 3D. He skilfully uses that 3D technology to frustrate any sense of a horizon or the horizontal – a tendency that can be found in a lot of modern art, from Pollock’s drip paintings to experimental film. Cuarón is not the first filmmaker to use this potential of 3D however. Werner Herzog played around with his 3D camera to dizzying effect in The Cave of Forgotten Dreams. And in Jean-Luc Godard’s 3D outing Adieu au langage, the French auteur explicitly addresses (albeit in a characteristically cryptic way) that same strand of disorientation. One of Godard’s characters floats this rhetorical question: “Right and left were inverted. But not the top and bottom. Why?”

It’s been a while since Gravity hit the silver screen. Why has it taken so long to make this audiovisual response? Well, for one, making a video essay takes time: it’s a protracted effort of finding the right footage, juggling it around while editing everything together, and fashioning a coherent argumentation from images and sound. That laborious process can make it hard to react instantaneously to any given film (5); this is where reviewers and scholars have the advantage.

But that time-consuming quality can be an advantage as well: video essayists can use the extra time for more considered contemplation and it can also give the added advantage of some historical perspective (as opposed to reacting in the moment). They can use their tardiness to revisit overlooked films (or unappreciated ones, which is what Scout Tafoya does so well in his video essay series The Unloved). Maybe that long-drawn-out production process is where the form’s true calling lies: using the video essay as a kind of slow cinema pendant to the immediacy of written reviews.

(1) Scott Foundas in Variety

(2) J. Hoberman in the New York Review of Books

(3) Kristin Thompson in a blog post for Observations on Film Art

(4) Thomas Elsaesser and Malte Hagener in the second edition of Film Theory: An Introduction Through the Senses

(5) In addition, video essay makers most often need the actual film to make their point, meaning they have to wait for it to be released on DVD or BluRay.

This video essay includes clips from:

Gravity [feature film] Dir. Alfonso Cuarón. Heyday Films et al., USA, 2013. 91 mins.

How It Feels to Be Run Over [short film] Dir. Cecil M. Hepworth. Hepworth, UK, 1900. 1 min.

The Cameraman [feature film] Dir. Edward Sedgwick. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer et al., USA, 1928. 69 mins.

Man with a Movie Camera [documentary] Dir. Dziga Vertov. VUFKU, Soviet Union, 1929. 68 mins.

Sunset Boulevard [feature film] Dir. Billy Wilder. Paramount Pictures, USA, 1950. 110 mins.

Jackson Pollock 51 [documentary short film] Dir. Hans Namuth. USA, 1951. 11 mins.

The Bad and the Beautiful [feature film] Dir. Vincente Minnelli. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, USA, 1952. 118 mins.

2001: A Space Odyssey [feature film] Dir. Stanley Kubrick. Stanley Kubrick Productions, UK et al., 1968. 149 mins.

La région centrale [experimental documentary] Dir. Michael Snow. Canada, 1971. 180 mins.

Capricorn One [feature film] Dir. Peter Hyams. ITC Films et al., USA, 1977. 123 mins.

Game Over: Kasparov and the Machine [documentary] Dir. Vikram Jayanti. Alliance Atlantis Communications et al., Canada et al., 2003. 90 mins.

Electric Edwardians: The Lost Films of Mitchell & Kenyon [documentary] British Film Institute, UK, 2005. 85 mins.

Cave Of Forgotten Dreams [documentary] Dir. Werner Herzog. Creative Differences et al., Canada et al., 2010. 90 mins.

Behind the Scenes – Gravity Mission Control [DVD extra] Buddha Jones et al., USA, 2013. 107 mins.

Behind the Scenes – Shot Breakdowns [DVD extra] Buddha Jones et al., USA, 2013. 37 mins.

Dawn of the Planet of the Apes: International Online VFX Primer Side By Side Clip [Featurette] Twentieth Century Fox, USA, 2014. 1 min.

The music used is:

‘Above Earth’, Gravity Original Motion Picture Soundtrack [music track, CD] Composer Steven Price. WaterTower Music, USA, 2013. 1 min 50 secs.

‘Aningaaq’, Gravity Original Motion Picture Soundtrack [music track, CD] Composer Steven Price. WaterTower Music, USA, 2013. 5 mins 09 secs.

‘Fire’, Gravity Original Motion Picture Soundtrack [music track, CD] Composer Steven Price. WaterTower Music, USA, 2013. 2 mins 58 secs.

‘Tiangong’, Gravity Original Motion Picture Soundtrack [music track, CD] Composer Steven Price. WaterTower Music, USA, 2013. 6 mins 29 secs.

‘Amazing Plan – Distressed’ [music track, digital download] Composer Kevin MacLeod . Incompetech.com, USA, 2010. 1 min 27 secs. Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License

The camera obscura images were found online at ClipArt ETC, Wikipedia and The Royal Society.

One additional film still was taken from:

Adieu au langage [feature film] Dir. Jean-Luc Godard. Wild Bunch et al., France, 2014. 70 mins.