Wuthering Heights: A Musical

Andrea Arnold’s film version of Wuthering Heights may well be the least literary adaptation of a literary work ever. Her take on Emily Brontë’s only novel does mince words. In fact, it almost does away with them: the dialogue is sparse and unforthcoming. Previous iterations of Heathcliff (as portrayed by Laurence Olivier, Timothy Dalton, Ralph Fiennes and so on) were well-spoken, even loquacious. Arnold’s Heathcliff would sooner swallow his tongue than be caught reciting romantic lines, and her Catherine Earnshaw is only slightly more talkative.

In the absence of words, Arnold looks for other modes of communication. She infuses her movie with alternative ways to relay meaning, intricately weaving together a large number of visual, auditory and even haptic motifs (1). There are the many animals that occur throughout the movie. (It’s not hard to connect a spirit animal or totem to each of the main characters). The changing seasons and countless close shots of Yorkshire moors flora are another visual reflection of the changing fortunes of the two lovers. And there’s the music.

When the film was released, the absence of music on the soundtrack was often mentioned. There are two problems with that statement. It is wrong. And it is wrong.

Commenters were referring to the lack of non-diegetic music, to the absence of a musical soundtrack in the classic sense. There is however non-diegetic music: Mumford & Sons wrote a song for the movie called The Enemy. That song not only plays over the end credits, but starts well before that – over the last scene of Arnold’s movie.

More importantly, there is diegetic music in the film. A lot of it. Catherine Earnshaw croons songs in no less than four separate scenes. Other characters too burst into song, on five different occasions. (It is interesting to note that the male characters are always heard singing as an ensemble, in church or at work in the fields. The female singers go solo). Finally, there are two occurrences of instrumental music: harp playing and the timely passage of an unseen but not unheard musical band performing the aptly mournful Coventry Carol. (Andrea Arnold and Catherine Earnshaw go to great lengths to point out that this band’s music is diegetic, mentioning them explicitly in the dialogue).

In all, this makes for almost a dozen instances of diegetic music in Arnold’s film. In fact, the lyrics sung are by far the longest lines of “dialogue” any character has in this movie. It is therefore not much of a stretch to say that Andrea Arnold’s Wuthering Heights is… a musical.

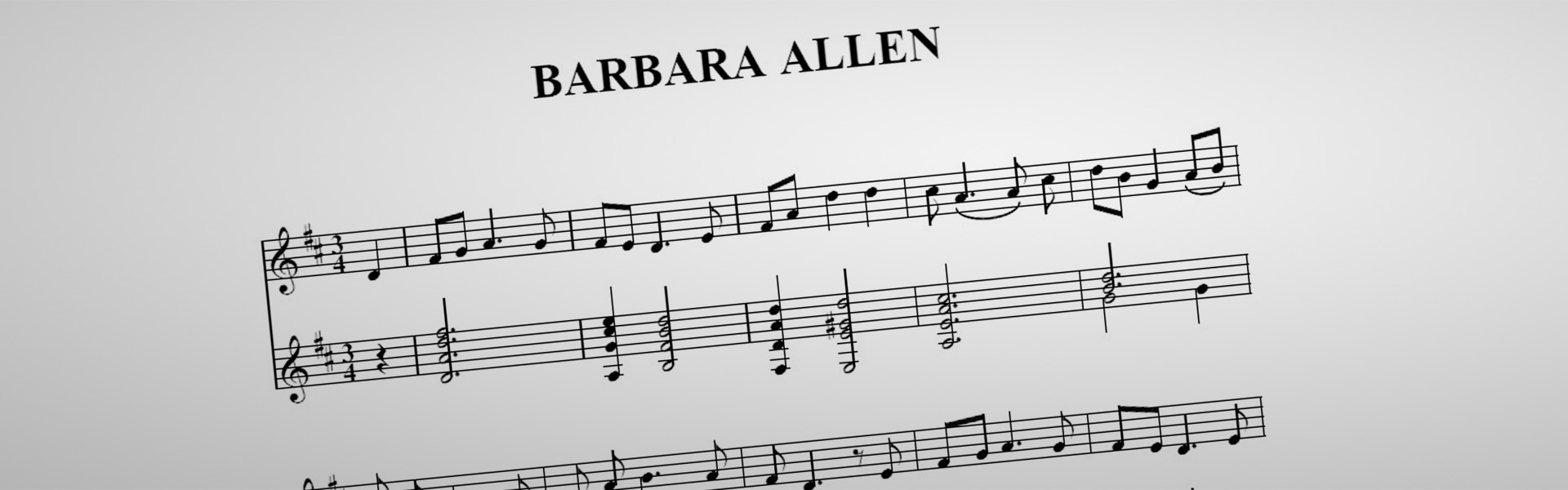

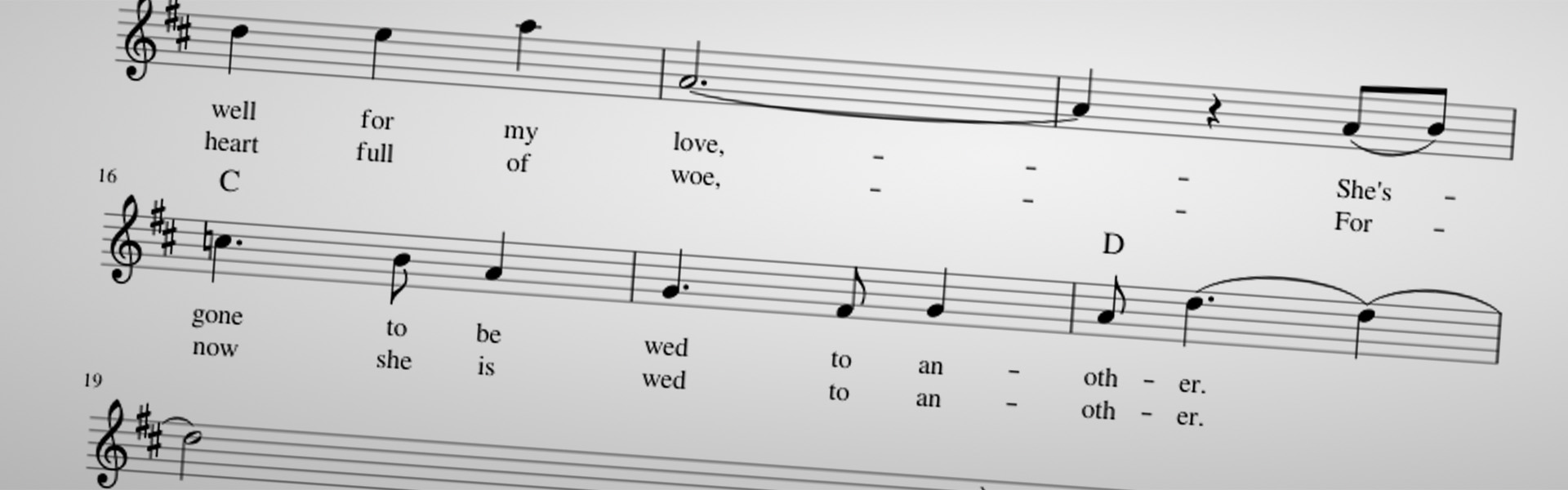

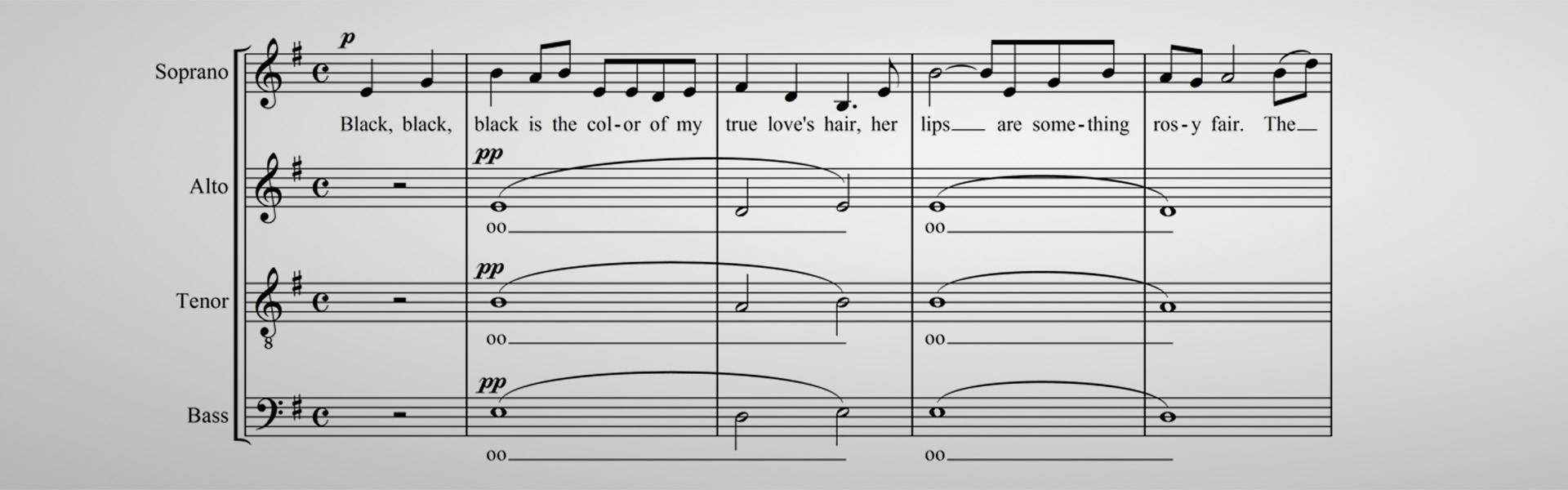

More importantly, those songs are yet another way of structuring and conveying the narrative, both through the melancholy nature of the music and through the lyrics. Arnold has carefully chosen traditional songs that can be understood as a reflection of the central dramatic tensions and plot elements. When Catherine sings the Ballad of Barbara Allen to her father, she is foretelling not only his death but also her doomed relationship with Heathcliff. The haunting The Cuckoo is sung as a lullaby to a weeping child, but its somber lyrics are an echo of the ill-fated romance between Heathcliff and Catherine. When the workers in the field belt out I Once Loved A Lass, that story of an untrustworthy woman is an indictment of Catherine. (The alternative title for that particular song is the very fitting The False Bride).

Each and every song reverberates throughout the images and actions of the film. Arnold’s visuals address the same topics as the ones mentioned in the lyrics, and expand on the feelings and tensions of the songs. The whole film, one could argue, is conceived as a tone poem. Its structure is a musical one rather than the classical linear narrative most movies adhere to.

This video essay tries to bring out that element of Andrea Arnold’s Wuthering Heights. It isolates most (not all) of the songs in the movie and uses that material to turn this wind-swept romance into a musical. The essay uses the same editing techniques as Arnold does, freely skipping between different time periods in the story and connecting scenes and images on the basis of visual and tonal parallels. The songs and the footage used have all been extensively rearranged (an apt term in this case, since this process involved an almost musical process of adaptation).

Does the end result tell the whole story? No, it doesn’t. None of the separate motifs and modes in Arnold’s film, when taken on their own, do so. Hers is an almost abstract rendition of the classic novel, an adaptation that tears down the language only to rebuild the story using different bricks. The mortar holding it all together, however, is the music.

(1) The emphasis Andrea Arnold puts on that haptic aspect is described in detail in a video essay by Luis Rocha Antunes and in his paper Adapting with the Senses – Wuthering Heights as a Perceptual Experience.

This video essay includes clips from:

Wuthering Heights [feature film] Dir. Andrea Arnold. Ecosse Films et al., UK, 2011. 129 mins.