Fear Freezes the Soul

Cinema is motion, as its etymological roots attest. But in the same manner that the invention of sound gave extra weight to silence (ask Robert Bresson), motion pictures can use immobility to great effect. A case in point is Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s 1974 melodrama Angst essen Seele auf (or Ali: Fear Eats the Soul).

Fassbinder updates Douglas Sirk’s All That Heaven Allows for mid-1970s German audiences (1). He keeps the basic plot: an older woman falls in love with a younger man, who also happens to be a few rungs below her on the ladder of social hierarchy. But Fassbinder adds racism to the mix, for his elderly protagonist Emmi loves and marries the Moroccan immigrant Ali. It allows him to serve up a critique of the prejudices of the working class in the (then) Bundesrepublik Deutschland. A critique that is is both blunt and elegant, both scathing and soothing.

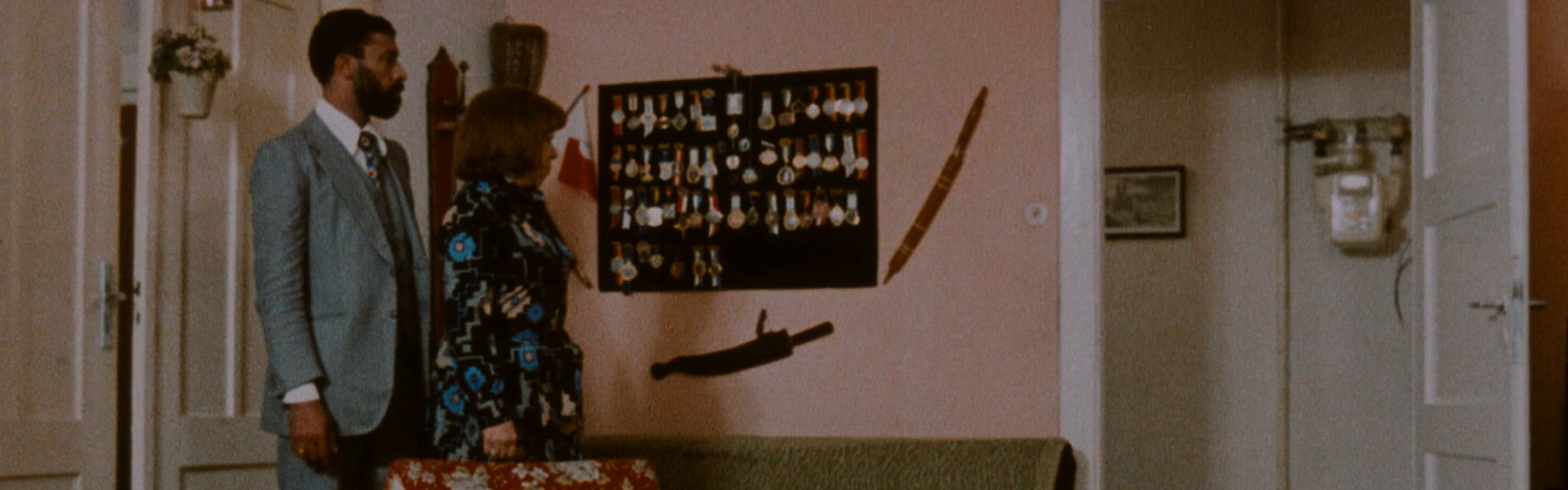

Emmi and Ali soon find that their relationship is met with disdain by their peers and superiors alike. They are moved by each other but the surrounding characters often freeze into immobility at the sight of the couple: they stand paralyzed as they stare contemptuously at Ali and Emmi. This stagnation becomes a powerful motif throughout the film. As the protagonists try to keep their relationship moving ahead, the world around them freezes into a spiteful standstill.

Fassbinder does not use freeze frames to achieve this effect (2). He has his actors simply stand motionless, echoing the visual tradition of the tableau vivant (3). They become living statues, immobilized by their own bigotry. Ali and Emmi are often the only characters moving; it’s no coincidence that their first meeting and later reconciliation are both set on a dance floor. When they have to face their own unfairness and infidelity in the middle part of the movie, they too risk slipping into inertia.

Angst essen Seele auf is often a motionless picture. An unmovie. But these moments are the stifled soul of the film: the stillness is almost suffocating in its impact. This video essay isolates those instances of inaction and tries to retell the complete story with only these frozen moments. A Hollywood executive would pitch this as Fear Eats the Soul meets La Jetée. We’re hoping this illustrates just how moving immobility can be.

(1) I’ve always loved how Fassbinder chose a title for this film that has the same cadence, even almost rhymes with Sirk’s title.

(2) He does use a freeze frame on one occasion in the movie. When Emmi introduces her new husband to her family, that predictably doesn’t go over well. Her relatives storm out of the door (after destroying her television set, in another nod to All That Heaven Allows). The next shot is of Ali and Emmi standing still, looking at the empty door. Fassbinder must have felt during editing that he needed a few extra seconds of immobility there, because the first couple of seconds of this shot are a freeze frame (you can tell by the change in the graininess).

(3) This peculiar stylization is also a nod to Bertolt Brecht’s views on acting as detailed in his thinking on the Epic Theater. Brecht didn’t want actors to fully become their characters, but instead play with a certain measure of detachment. The resulting Verfremdungseffekt (distancing effect) would keep the audience from identifying with the characters, and prompt them to focus on the (ideological) message of the play. Undoubtedly, Fassbinder had the same ideological goals. Finally, it is interesting to note that Douglas Sirk, when he was still working in Germany, directed Brecht’s Threepenny Opera.

This video essay includes clips from:

Angst essen Seele auf [feature film] Dir. Rainer Werner Fassbinder. Filmverlag der Autoren et al., Germany, 1974. 94 mins.

The music used is: